[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake (Tantilla wilcoxi)

[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”2098″ img_size=”large” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded”][vc_column_text]Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake, Sierra Los Ajos, Sonora. Photo by Larry Jones[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”2281″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake, Huachuca Mtns, AZ. Photo by Jim Rorabaugh[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”2282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake, Huachuca Mtns, AZ. Photo by Jim Rorabaugh[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]

Description

The Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake (Tantilla wilcoxi) was described by Leonhard Stejneger (1903) of the Smithsonian Institution from a juvenile male collected by Timothy E. Wilcox M.D. at Fort Huachuca in 1892 (USNM 19674). Based primarily on variation in numbers of ventral and subcaudal scales, Smith (1942) described two subspecies, but that classification is not accepted by recent authors (Cole and Hardy 1981, Ernst and Ernst 2003, Crother 2012).

Black-headed Snakes in our area, of which there are four species, are not commonly encountered, but fewer Chihuahuan Black-headed Snakes have been collected from Arizona (22 museum specimens) than the other three species by far. Only four records exist for Sonora. In the 100-Mile Circle, this is a small and secretive species of the sky islands with an apparently limited and patchy distribution.

Description and Similar Species

The Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake is a slender and small (< 356 mm total length, tail length is 24-26% of total length), light tan, brown, or yellowish-brown snake dorsally with a dark gray-brown cap on the top of the head that extends to or below the corner of the mouth (Fig. 1 and 2). A distinct off-white or pale cream collar, two scale rows wide, is always present immediately posterior to the dark head cap. The anterior portion of the light collar crosses the tips of the parietal scales. That collar is bordered posteriorly and often anteriorly by a thin gray-brown band or dotted lines that are typically darker than the head cap and 0.5-1.5 scale rows wide. The supralabials are mostly white, and that color expands posterior to the eye so that all of the fifth and usually part of the sixth supralabials are white, forming a light cheek patch (Fig. 2). Minute dark spots or maculations are present on the dorsal scales. The venter lacks spots, and is cream or white anteriorly, grading to light pink or orange posteriorly. All Tantilla lack loreal scales. This description is based on the following sources: Cole and Hardy (1981), Wilson (1982), Liner (1983), Ernst and Ernst (2003), Brennan and Holycross (2006), and Lemos-Espinal and Smith (2007a, b).

In our area, the Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake is most easily confused with other species of Tantilla, particularly the Yaqui Black-headed Snake (T. yaquia). However, in that species the light collar does not touch the parietal scales and there is no dark line or row of spots immediately posterior to the light collar. Both the Yaqui and Chihuahuan Black-headed Snakes have light cheek patches, but in the former, all of the sixth supralabial is white, whereas in the latter the dark head cap usually intrudes onto the sixth supralabial. In Smith’s Black-headed Snake (T. hobartsmithi) the light collar is often absent, or if present it is often faint or thin. Furthermore, that light collar does not touch the parietal scales and a dark band or row of dots is not present posterior to it. The Plains Black-headed Snake (T. nigriceps) does not have a light collar. The minute dark spots on the dorsal scales present in the Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake are also present in Smith’s Black-headed Snake, but are absent in the Yaqui and Plains Black-headed Snakes. The Ring-necked Snake (Diadophis punctatus) is superficially similar to the Black-headed Snakes, but it has loreal scales (may be missing on one side) and dark spots on the ventral surface.

Figure 2: Same snake as in Figure 1, illustrating distinctive scalation and coloration characters on the head.

Distribution and Habitat Use

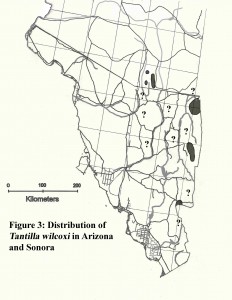

In Arizona, the Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake is known primarily from the Huachuca Mountains, where it has been collected at Fort Huachuca and in Carr, Miller, Ramsey, Copper, Scotia, and Sunnyside canyons, near “Igo Ranch”, and at several unspecified localities. It is known from Gardner and Madera canyons in the Santa Rita Mountains, and the ghost town of Mowry in the Patagonia Mountains. Two specimens from the Sierra San Luis, Mexico, suggest the species could occur in the Peloncillo Mountains of Arizona and New Mexico, although woodland habitats preferred by the species are scarce in that range and have been degraded by prescribed fires set by the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management in recent decades. Elevations of Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake localities in Arizona range from 1545 to 1875 m. In Sonora, the species is known only from the Sierras San Luis and Bacadéhuachi, and the mountains west of Yécora, although it has likely been overlooked in several other areas (Fig. 3).

Elsewhere, the species is known from western Chihuahua south and east to northern Sinaloa, central Durango, southeastern Coahuila, southern Zacatecas, Nuevo Leon, and San Luis Potosí at elevations of 900-2436 m (Ernst and Ernst 2003, Lemos-Espinal and Smith 2007a,b, Rorabaugh 2008).

Of the four species of Tantilla found in Arizona, the Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake is the most specialized in terms of habitat use. Throughout its range, it is primarily a species of montane canyons and slopes in oak or pine-oak woodland. Although Stebbins (2003) and Lowe (1964) report that its distribution extends into desert or semi-desert grasslands, all Arizona and Sonora localities are within montane woodlands. Most specimens are found under rocks, dead yuccas, agaves, sotols, or other surface debris.

Activity and Behavior

Arizona and Sonora collections and observations have occurred from early March to late September, although most are found in July and August. The behavior of this species is little known, but as a group, North American Tantilla are generally considered primarily nocturnal, fossorial species that spend much time foraging for prey in leaf litter and under debris. It presumably is dormant during the winter months.

Behler and King (1979) reported that females lay clutches of 1-3 eggs. Goldberg (2004) found a single egg in the oviduct of a female collected in Arizona on 22 September. Eight males (four from Arizona, four from Mexico) collected July-September were undergoing spermiogenesis, the smallest male of which was 168 mm SVL (Goldberg 2004). Wright and Wright (1957) reported that the smallest mature males and females were 214 mm and 175 mm (presumably total length), respectively.

Diet

The diet of this species has not been specifically studied, but as with other Tantilla in our area, it probably feeds upon spiders, insect larvae, millipedes, centipedes, and scorpions (Fowlie 1965, Behler and King 1979, Stebbins 2003, Lemos-Espinal and Smith 2007a).

Although not investigated in this species, Tantilla have enlarged, grooved teeth in the rear of the upper jaw capable of delivering toxic secretions from the Duvernoy’s gland to prey items. This species is harmless to humans and does not attempt to bite.

Conservation

The Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake is listed as a species of least concern on the IUCN’s Red List. However, its montane woodland habitats are at risk in Arizona from wildfire and climate change. Major stand-replacing fires in the Huachuca and Santa Rita mountains over the last 40 years have degraded the habitat of this species, while in some areas of Mexico forested habitats of the Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake have been heavily logged. Mining can eliminate habitat of this species locally.

Literature Cited

Behler, J.L., and F.W. King. 1979. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY.

Brennan, T.C., and A.T. Holycross. 2006. Amphibians and Reptiles in Arizona. Arizona Game and Fish Department, Phoenix, AZ.

Cole, C.J., and L.M. Hardy. 1981. Systematics of North American colubrid snakes related to Tantilla planiceps (Blainville). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 171(3):199-284.

Crother, B.I. 2012. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico, with comments regarding confidence in our understanding, seventh edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, Herpetological Circular (39):1-92.

Ernst, C.H., and E.M. Ernst. 2003. Snakes of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.

Fowlie, J.A. 1965. The Snakes of Arizona. Azul Quinta Press, Fallbrook, CA.

Goldberg, S.R. 2004. Tantilla wilcoxi (Chihuahuan Black-Headed Snake). Reproduction. Herpetological Review 35(1):73.

Lemos-Espinal, J.A., and H.M. Smith. 2007a. Anfibios y Reptiles del Estado de Coahuila, Mèxico/Amphibians and Reptiles of the State of Coahuila, Mexico. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mèxico y Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Mexico.

Lemos-Espinal, J.A., and H.M. Smith. 2007b. Anfibios y Reptiles del Estado de Chihuahua, Mèxico/Amphibians and Reptiles of the State of Chihuahua, Mexico. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mèxico y Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Mexico.

Liner, E.A. 1983. Tantilla wilcoxi. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 345:1-2.

Lowe, C.H (ed.). 1964. The Vertebrates of Arizona. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ.

Rorabaugh, J.C. 2008. An introduction to the herpetofauna of mainland Sonora, México, with comments on conservation and management. Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science 40(1):20-65.

Smith, H.M. 1942. A resume of the Mexican snakes of the genus Tantilla. Zoologica (New York) 27:33-42.

Stebbins, R.C. 2003. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians, third edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, MA.

Stejneger, L. 1903. The reptiles of the Huachuca Mountains, Arizona. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 25:149-158.

Wilson, L.D. 1982. Tantilla. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 307:1-4.

Wright, A.H., and A.A. Wright. 1957. Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada. Volumes I and II. Comstock Publishing Associates, Cornell University Press, New York, NY.

Author: Jim Rorabaugh

Originally published in the Sonoran Herpetologist 2013 26(4):77-79.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][gap size=”30px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column][/vc_row]